In the past two years, I have replaced many of the consumer software programs I use with software that I write and maintain myself. One happy consequence has been that whenever a program lacks a feature I want, I can simply implement it myself. Another is that I have been able to tightly integrate many of the programs I use into a single system. I call this system Khaganate.

Khaganate includes:

- a habit tracker

- a task tracker

- a goal tracker

- a personal finance spreadsheet

- a reading and watching log

- a calendar app

- a journal

- a bookmarks manager

- go links

- a metrics dashboard

- a spaced-repetition quiz system

- a file explorer

- a search index

- a travel map

This post describes what Khaganate does and how I use it. In next week's post, I detail the tools and technologies I used to build Khaganate.

The post is illustrated with many screenshots of Khaganate's interface. I have redacted some information for the sake of my personal privacy, but otherwise the screenshots show Khaganate exactly as it appears in my daily use. If you have JavaScript enabled, you can expand the images by clicking on them.

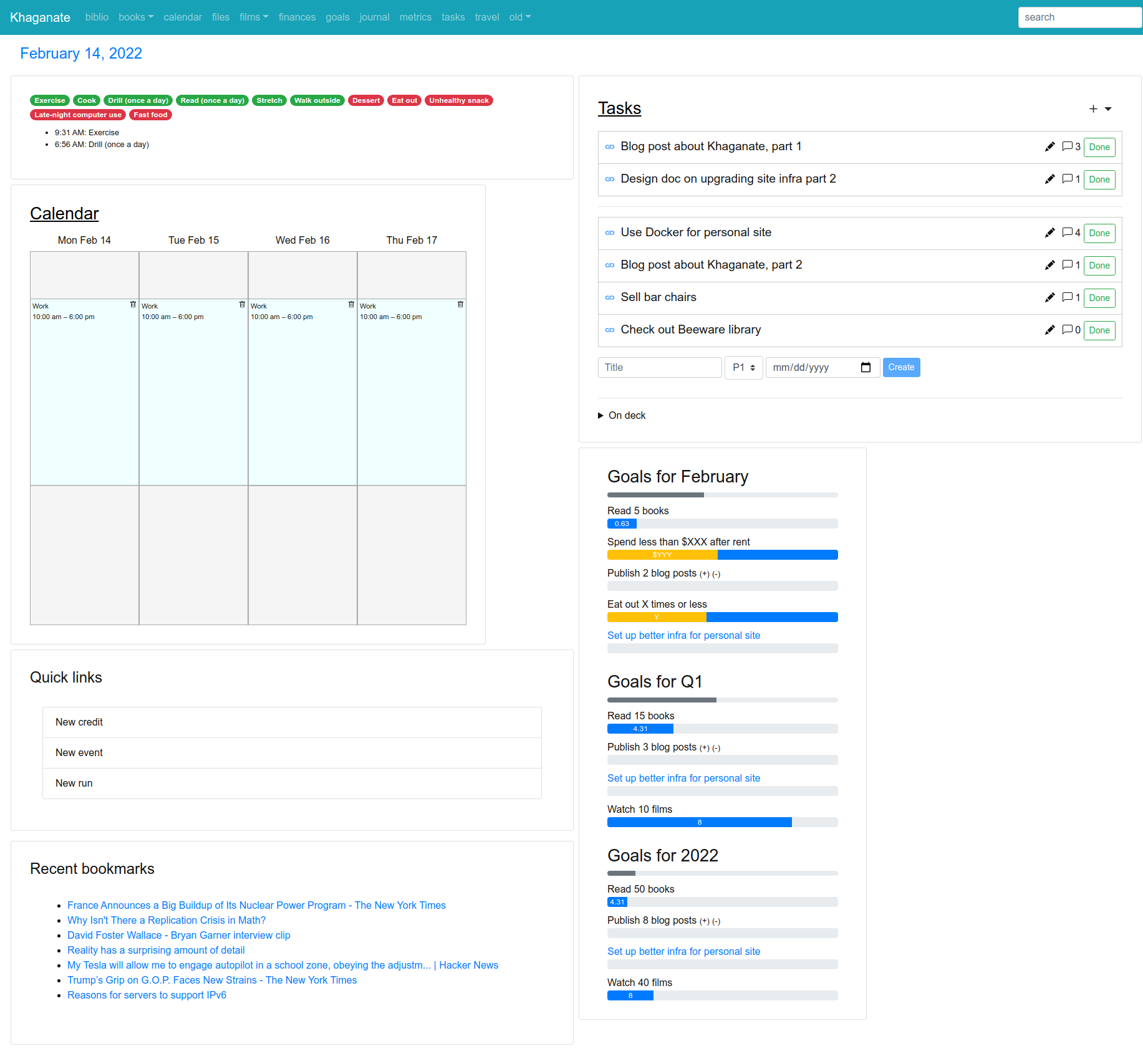

Home page

The first thing I do after I power on my computer in the morning is start the Khaganate server locally and open up Khaganate's home page in my browser. (I run Khaganate locally because it's simpler and more secure than hosting it on the internet.)

The home page includes a habits tracker, a task inbox, a calendar, and a goals box, each of which will be covered in their own sections. At bottom left are a few useful links — recording expenses and exercise, and adding events to my calendar — and a list of recently bookmarked links.

Habits

I'd used habit trackers for several years before starting Khaganate, mostly the excellent Loop Habit Tracker for Android. The first iteration of the Khaganate habit tracker was similar to Loop, with a set cadence for each habit and a grid of daily checkmarks. I switched to a linear view because it takes up less space and allows me to record multiple instances of the same habit in a single day. Each habit carries a certain number of points, and I track the total points from good and bad habits on my metrics dashboard. The individual habits are also useful as their own metrics (e.g. "How many times did I cook this month?"), and for setting goals that can be tracked automatically (for example, "Eat out less than X times a month").

Tasks

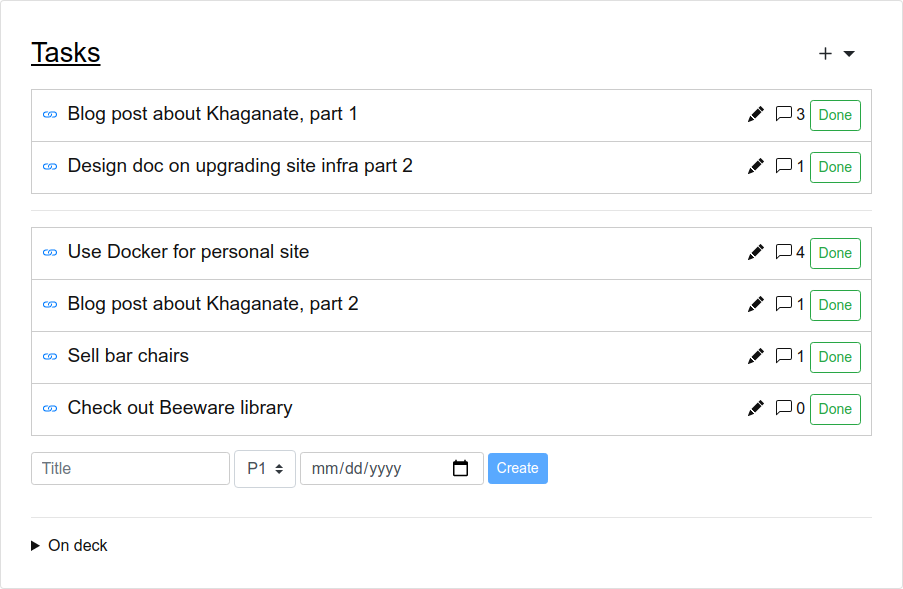

Also on the home page is my task inbox. The screenshot above shows six tasks in the inbox. The two high-priority tasks are separated from the four lower-priority tasks by a horizontal line. There is an inline form at the bottom to quickly create new tasks, and a button next to each task to mark it as done. I found that it is essential for the experience to be as frictionless as possible, or else I won't use the task tracker consistently.

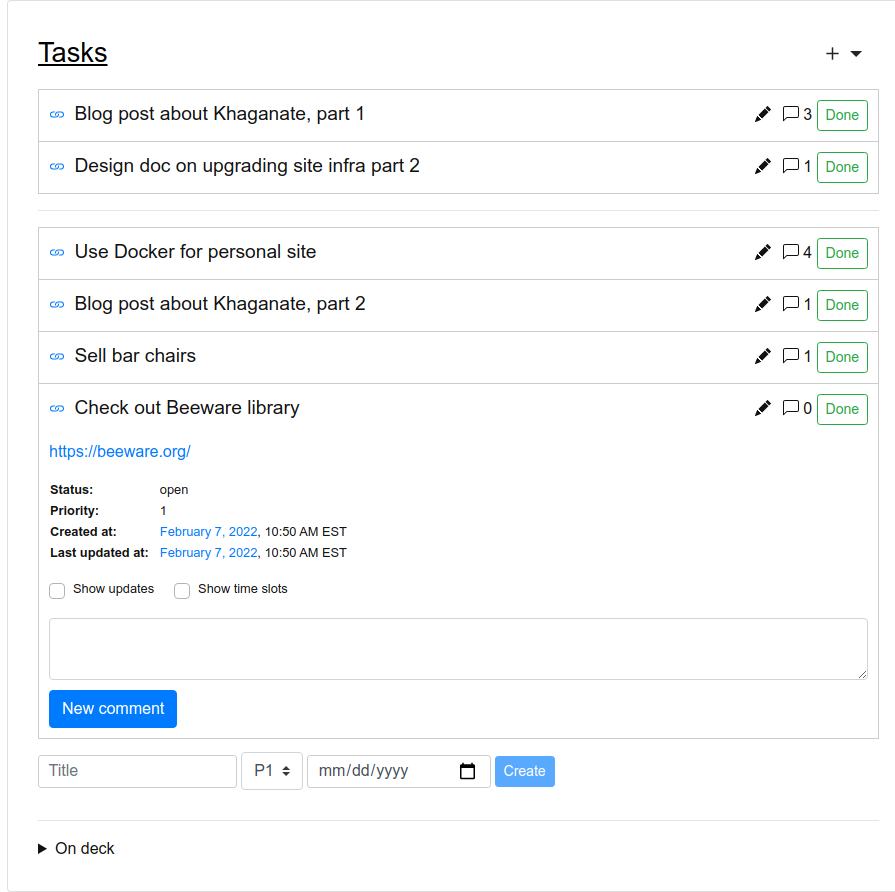

The task boxes on the home page are expandable. The screenshot below shows the "Check out Beeware library" task expanded.

Tasks can have a description (like most free-form text in Khaganate, it is rendered as Markdown) and an unlimited number of comments. Tasks have a status field (open, fixed, won't fix, obsolete, or duplicate) and a priority from 0 to 4. They may also have a deadline, which will cause them to show up in the task inbox regardless of their priority if the deadline is impending.

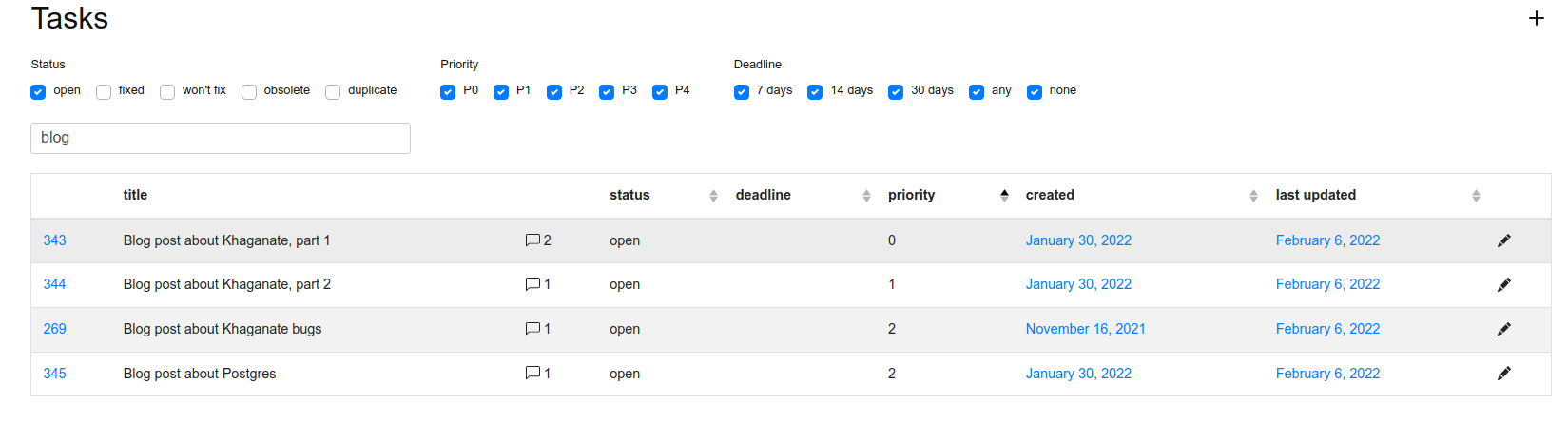

There is a dedicated page which lists all the tasks:

In the screenshot, the list is filtered by a search query which matches against the task's title. It can also be filtered by status, priority, and deadline.

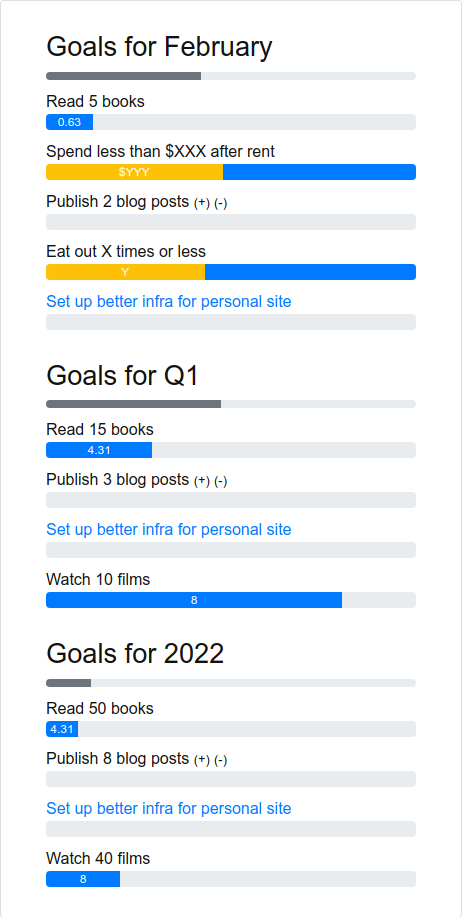

Goals

I use Khaganate to track monthly, quarterly, and yearly goals. Many of these goals are tracked automatically: for instance, the progress bar for "Read 5 books" is auto-filled from my reading log within Khaganate, and "Set up better infra for personal site" is tied to the status of a task in the task tracker. Other goals, like "Publish 2 blog posts", have to be updated manually. The gray progress bar at the top of each section shows how much time has elapsed in that month, quarter, or year.

Finances

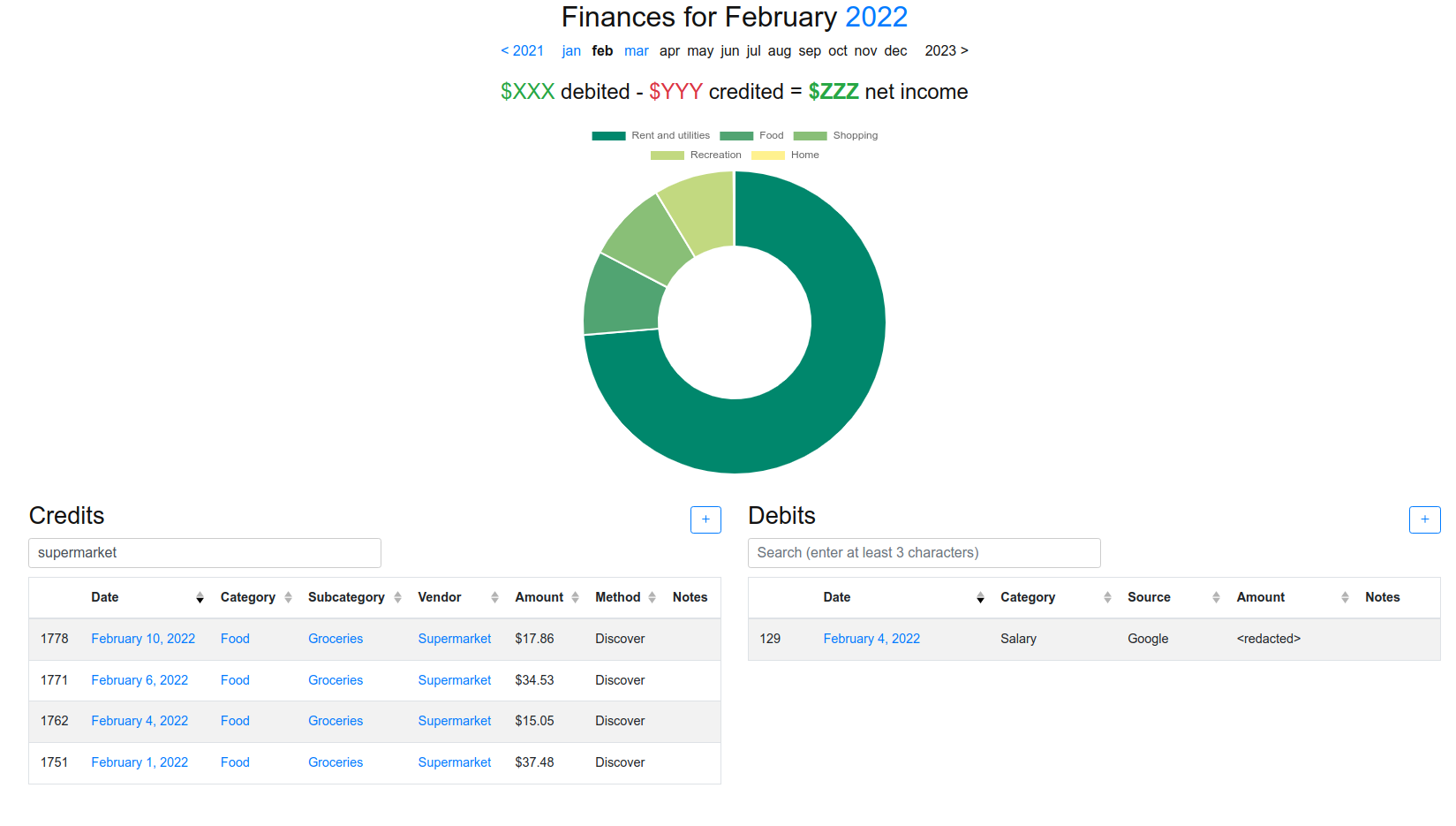

One of the first systems I built in Khaganate was a personal finances spreadsheet.

The month log page shows my total income and expense, with a pie chart breaking it down by category. I categorize everything in two levels, e.g. "Food / Groceries" or "Shopping / Technology"; the pie chart only shows the primary categories. Below the chart are two tables listing my credits and debits line-by-line, along with buttons to open a modal form to record new credits and debits.

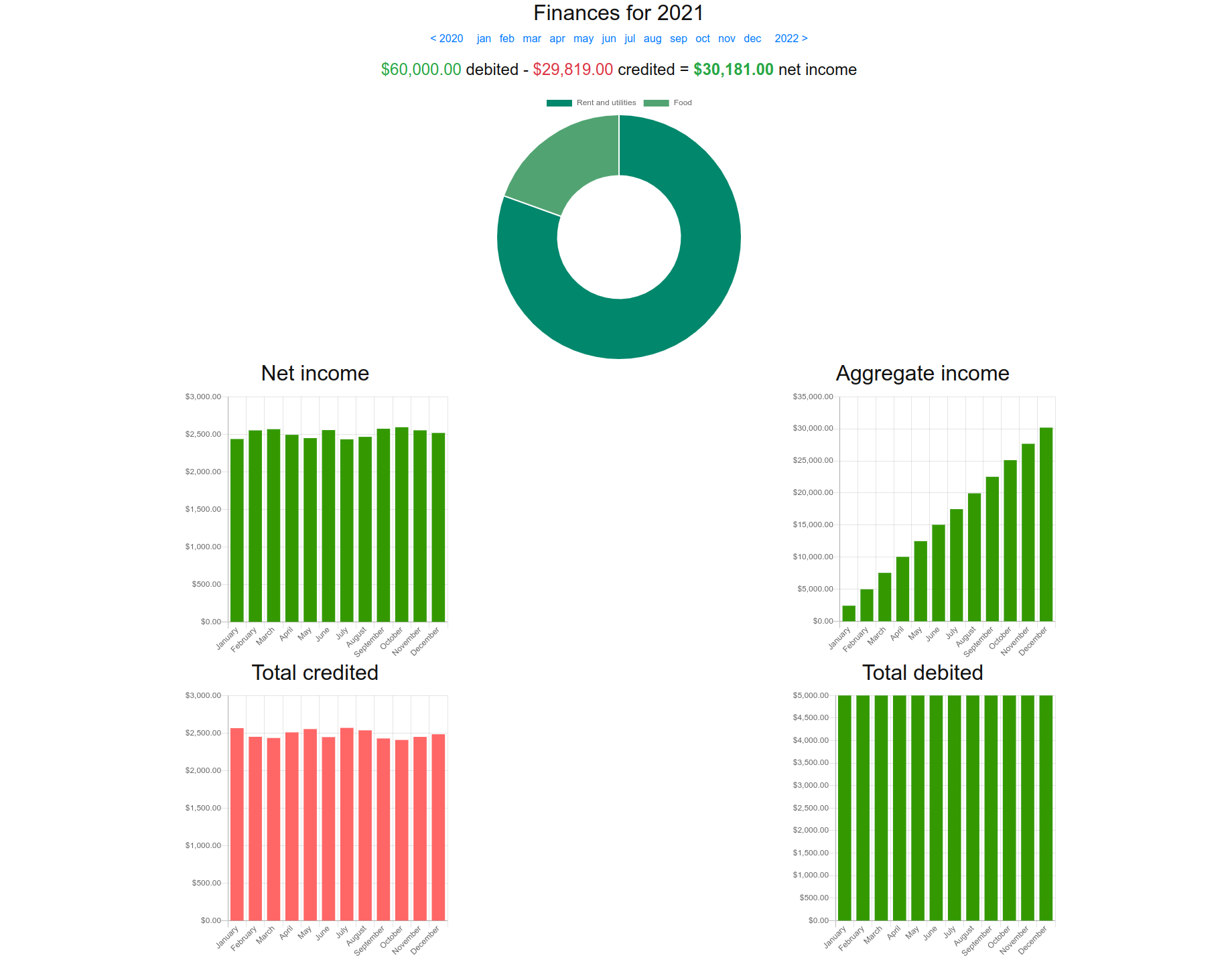

There is also a yearly summary page:

It was too hard to partially redact my real data, so I just populated the interface with fake data. In a real year, there would be closer to a dozen categories in the pie chart. I don't check this page often, but it's helpful to have the data so I can look back at years of financial information when I need to.

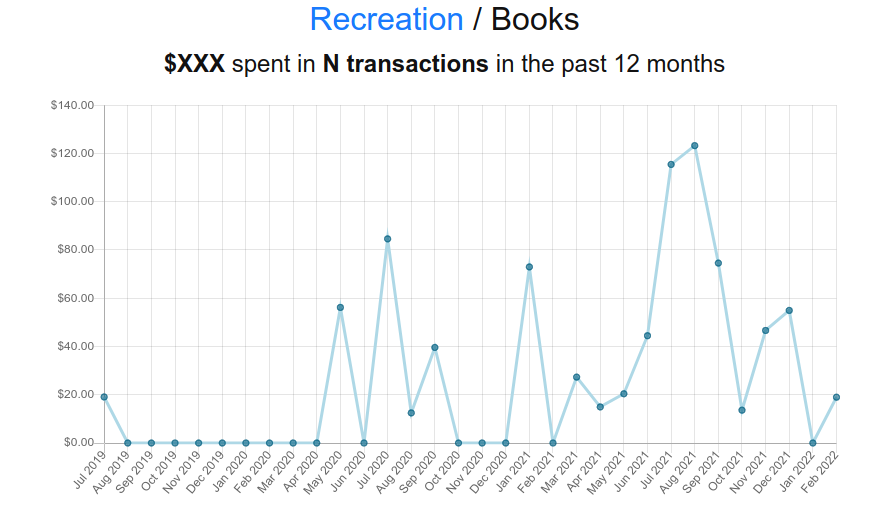

Each category and subcategory has its own page that shows spending in that category over time.

Books and films

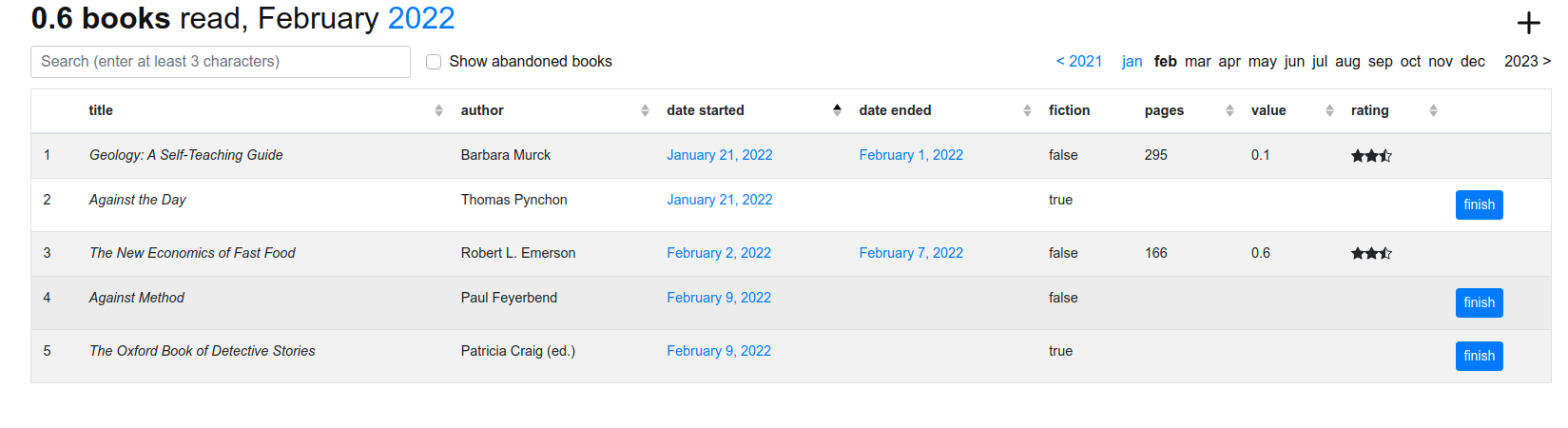

I use Khaganate to record the books that I read and the films that I watch. Pictured above is my reading log for the month of February 2022; a similar page exists for films, and there are yearly and lifetime summary pages.

The number of books read is adjusted for both the length of the book and the time during the month. For example, the first book, Geology: A Self-Teaching Guide, was mostly read in the previous month, so it only counts as 0.1 books for February.

Calendar

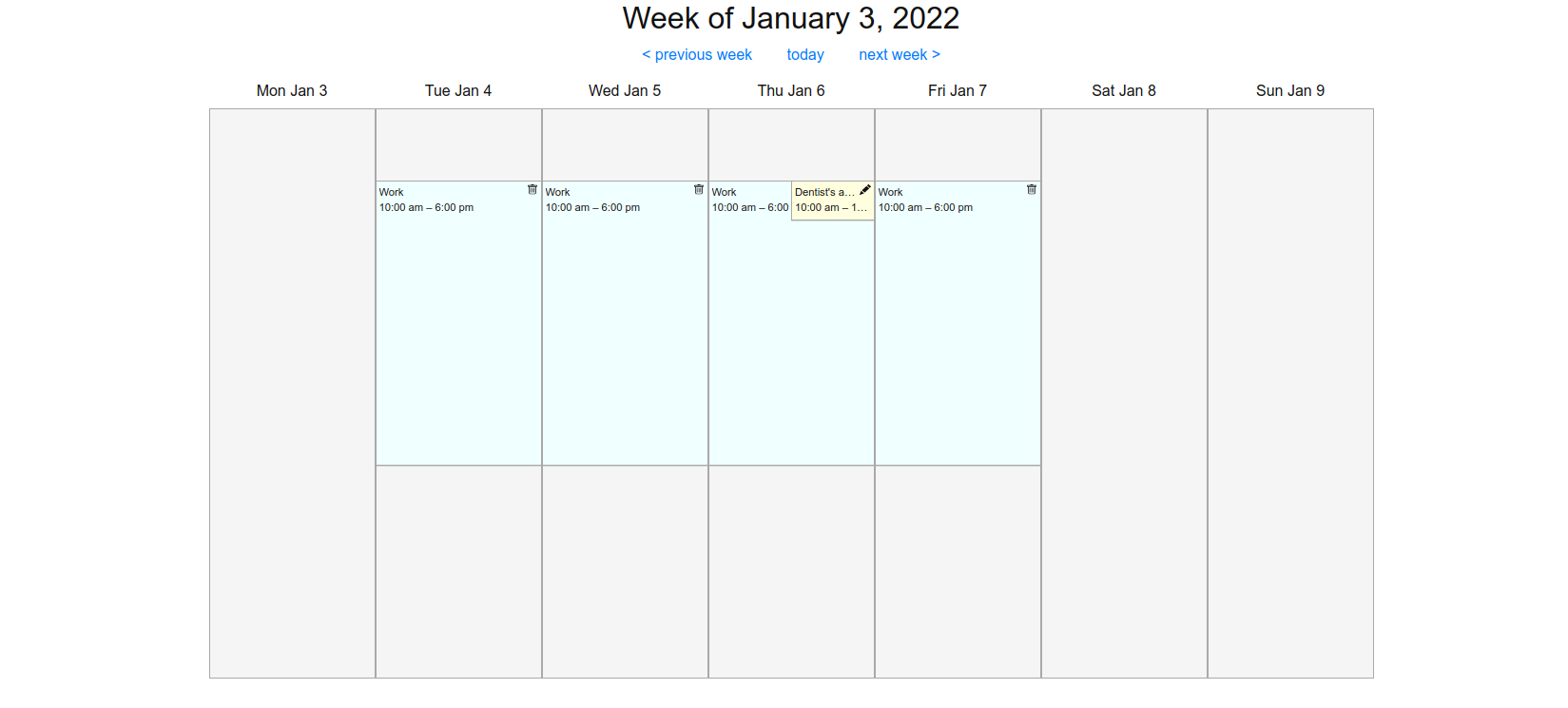

I built a simple calendar app inside Khaganate because I was frustrated with Google Calendar. The main benefit is that it appears on Khaganate's home page, which I check every morning. It isn't too fancy, but it does support recurring as well as one-off events, and exceptions for recurring events (e.g., no work because of a holiday, or skipping a weekly meeting). Events can have extended descriptions, as well as added time for travel which shows up before and after the event on the calendar. Events can have a location, which will turn the event title into a hyperlink to Google Maps.

Journal

I keep a regular journal that is stored in Khaganate's database. The journal page is barebones, so I haven't included a screenshot, but it does include my calendar for that day, the books I was reading, and any expenses I incurred, as well as the actual text of the journal entry if there is one.

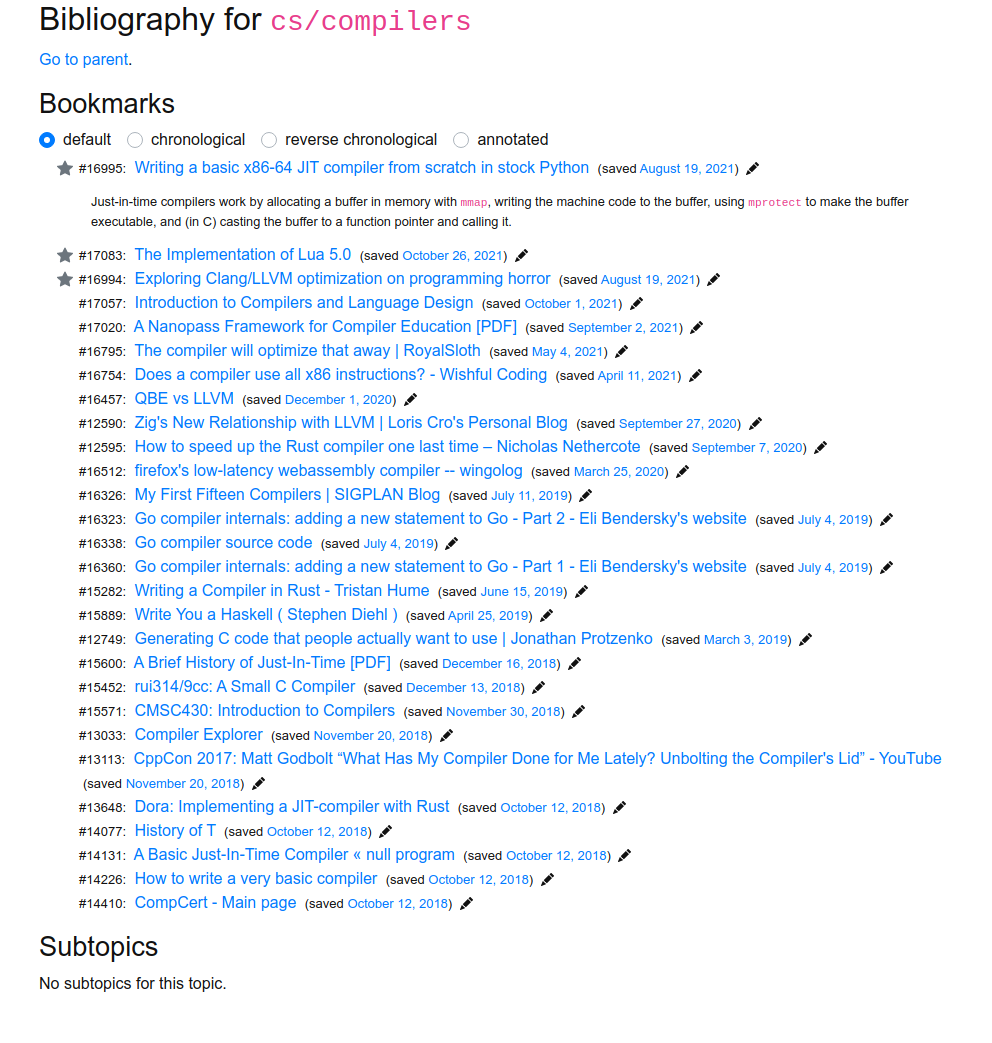

Bookmarks

I found both Firefox's and Chrome's built-in bookmarking tools to be limited, so I wrote my own. It's a browser extension (triggered by Alt+D in Chrome) with a similar interface to the built-in bookmark form, with a few optional extra fields like author, year, keywords, and topics. I can also add a long-form Markdown annotation (usually a brief summary of the main points).

Then, I can see all bookmarks organized by topic, pictured below. Unlike bookmark folders, a single bookmark can be associated with multiple topics.

Bookmarks can be marked as good or excellent quality, which causes them to show up higher in the list above.

Go links

I wrote about go links in an earlier blog post. The example code in the blog post uses a Flask server; on my own computer, the go links server is part of Khaganate. Besides a database of hard-coded go links like go/weather, there are also parameterized links like go/python/XYZ, which takes me to the documentation for the XYZ module in Python's standard library, and other short links like w/XYZ, which takes me to the article "XYZ" on Wikipedia.

As explained in the blog post, a browser extension is required to redirect short links to the Khaganate server.

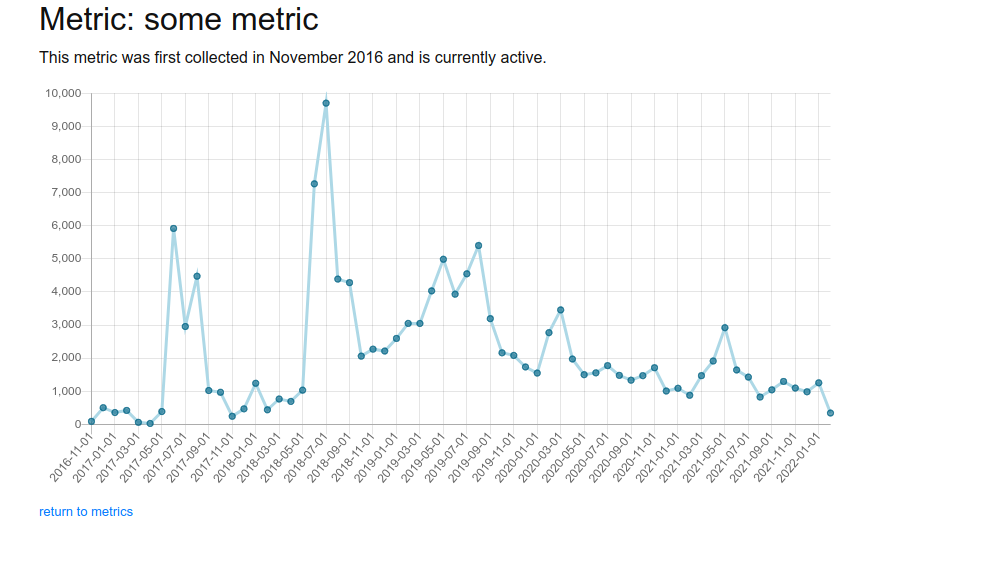

Metrics

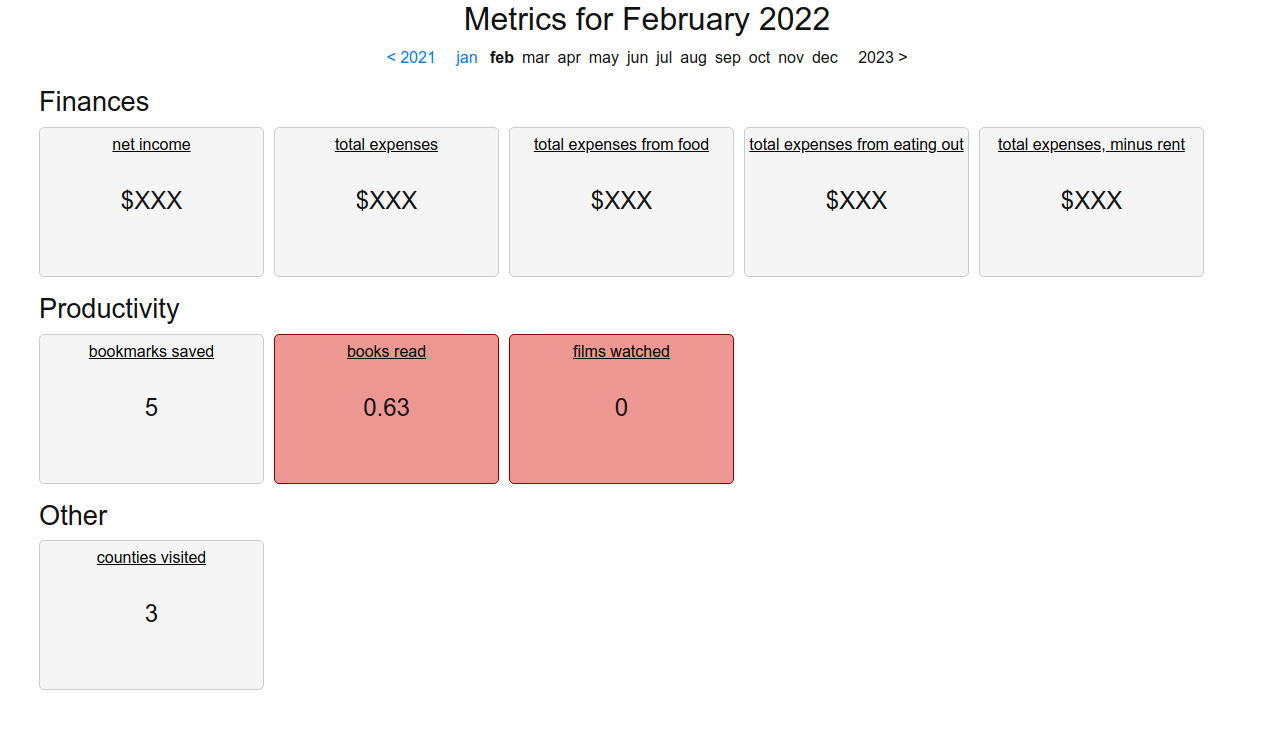

Khaganate includes a metrics dashboard that pulls data from various other components:

Each metric has its own detail page with a graph of its value over time.

Drill

I earlier wrote a command-line tool to take spaced-repetition quizzes. I ported this to Khaganate to unlock new possibilities, mainly the ability to display images in quizzes (although I haven't implemented this yet).

Files

Most of my important files live in a files/ directory in my home folder. It is tracked by git, and a cron job running once an hour automatically commits any unstaged changes. The cron job also pushes the changes to a remote repository, which serves as an auxiliary data back-up.

Khaganate contains a file browser that allows me to view and edit files and examine their revision history. I tend to still use the shell and vim for file management, but the file browser does allow me to link directly to files elsewhere in Khaganate. For example, I can take notes on a book and then link to the notes file from the reading log.

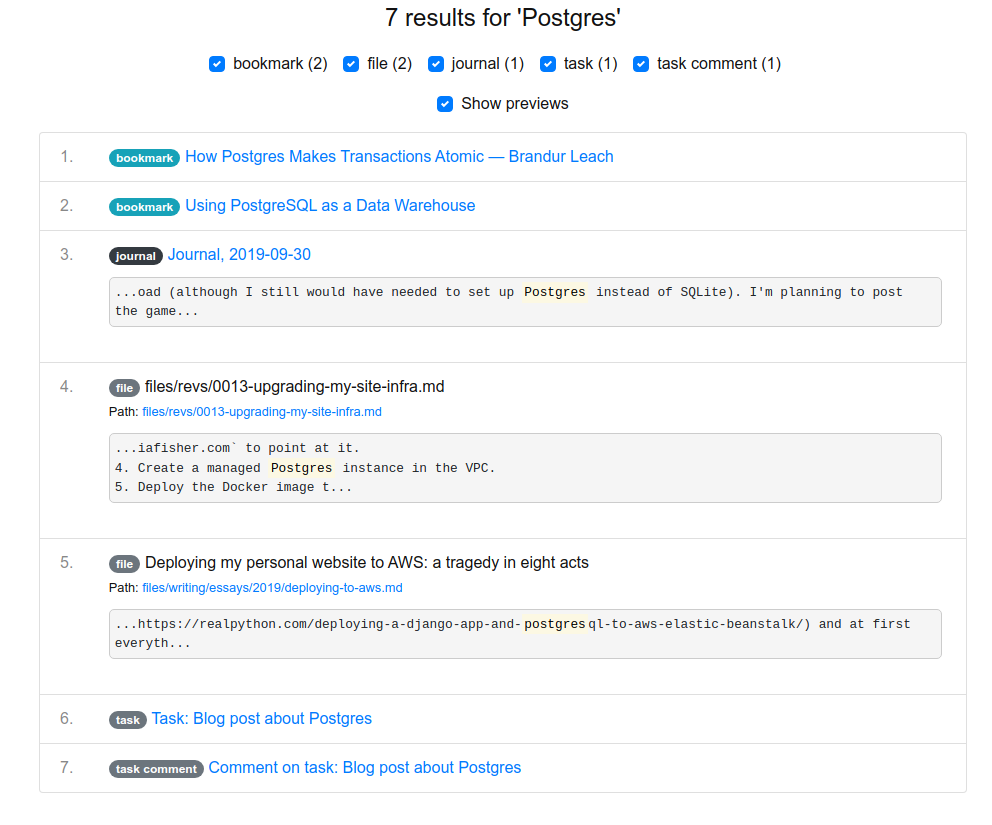

Search

Almost everything in Khaganate is searchable: bookmarks, files, tasks, journal entries, financial transactions, and more.

Travel

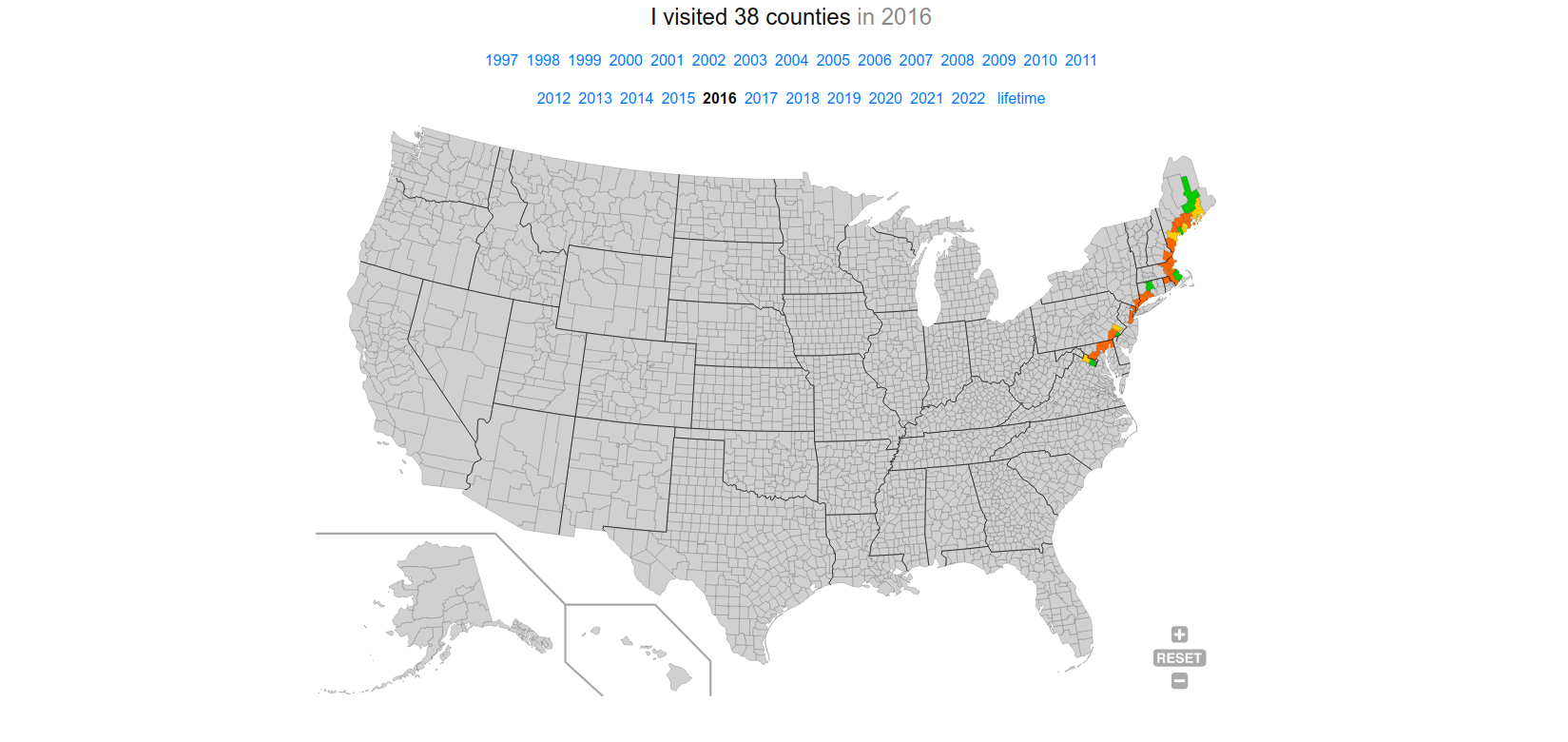

I previously kept an SVG map of U.S. counties that I had visited, which I had to manually edit every time I visited a new county. With the advent of Khaganate, I was able to turn the travel map into a web app. Now I can click on a county on the map to open a form to record a visit there, instead of having to open up an SVG editor.

The screenshot above is for 2016, when I went on a road trip to Maine. Green counties are those where I spent the night; yellow where I visited; and orange where I only traveled through. (I wasn't recording county visits at the time — I reconstructed the route years after the fact, which is why parts of the map are disconnected.)

The travel map is mostly independent of the rest of Khaganate, but it's neat to look at.

Conclusion

Sometimes while working on Khaganate I think of the xkcd comic about whether or not it is worth it to make routine tasks more efficient. I've certainly spent a lot of time on Khaganate — the git repository has more than 2,300 commits since November 2019. Has it been worth it?

I think it has. If I hadn't built Khaganate, then tracking my tasks and goals would be much harder. I wouldn't be able to remember what I had read and watched. I would know little about my spending habits. (Khaganate was essential in helping me analyze why I spent much more money in 2021 than in 2020.) My bookmarks would be less organized. I'd be more beholden to external services like Google Calendar.

I don't expect that Khaganate would be useful to or desirable for everyone, and I don't intend to maintain it as an open-source project. However, to accompany this blog post I have published a one-time scrubbed snapshot of the code, in case anyone wants to use it as a starting point or inspiration for their own project. You can find it at https://github.com/iafisher/khaganate-snapshot. It is released under the MIT license, so you are welcome to do with it whatever you wish. ∎